symmetric

skew-symmetric

unitary

null

Given \(A = [a_{ij}]_{3 \times 3}\), where \(a_{ij} = (i - j)^3\).

1. Diagonal elements (\(i = j\)): \(a_{ii} = (i - i)^3 = 0\). 2. Off-diagonal elements (\(i \neq j\)): \[a_{ji} = (j - i)^3 = (-(i - j))^3 = -(i - j)^3 = -a_{ij}\]

Since \(a_{ii}=0\) and \(a_{ij} = -a_{ji}\), the matrix \(A\) is a skew-symmetric matrix.

The correct option is B. skew-symmetric.

Consider the following two statements:

Statement 1: \(e^\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of \(e^A\).

Statement 2: \(\mathbf{v}\) is an eigen-vector of \(e^A\).

Which one of the following options is correct?

Statement 1 is true and statement 2 is false.

Statement 1 is false and statement 2 is true.

Both the statements are correct.

Both the statements are false.

The relationship is \(A\mathbf{v} = \lambda\mathbf{v}\). Using the Maclaurin series for \(e^A\): \[e^A \mathbf{v} = \left( I + A + \frac{A^2}{2!} + \cdots \right) \mathbf{v} = \left( 1 + \lambda + \frac{\lambda^2}{2!} + \cdots \right) \mathbf{v}\] \[e^A \mathbf{v} = e^\lambda \mathbf{v}\] This confirms that \(\mathbf{v}\) is the eigenvector and \(e^\lambda\) is the corresponding eigenvalue of \(e^A\). Both statements are correct.

The correct option is C. Both the statements are correct.

\(x \in (1, 2)\)

\(x \in (2, 3)\)

\(x \in (0, 1)\)

\(x \in (0.5, 1)\)

For \(f(x)\) to be decreasing, \(f'(x) < 0\). Using the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus: \[f'(x) = \frac{d}{dx} \int_{0}^{x} e^t (t-1)(t-2) dt = e^x (x-1)(x-2)\]

We require \(e^x (x-1)(x-2) < 0\). Since \(e^x > 0\), we need \((x-1)(x-2) < 0\). This inequality holds when \(x\) is between the roots 1 and 2, i.e., \(\mathbf{1 < x < 2}\).

The correct option is A. \(x \in (1, 2)\).

The matrix \(A\) satisfies the equation \(6A^{-1} = A^2 + cA + dI\), where \(c\) and \(d\) are scalars and \(I\) is the identity matrix.

Then \((c + d)\) is equal to

5

17

\(-6\)

11

The characteristic equation \(\det(A - \lambda I) = 0\) is: \[(1-\lambda) [ (4-\lambda)(1-\lambda) - (-2)(1) ] = 0 \implies \lambda^3 - 6\lambda^2 + 11\lambda - 6 = 0\] By Cayley-Hamilton Theorem: \(A^3 - 6A^2 + 11A - 6I = \mathbf{0}\). Multiplying by \(A^{-1}\): \(A^2 - 6A + 11I = 6A^{-1}\).

Comparing \(6A^{-1} = A^2 + cA + dI\) with \(6A^{-1} = A^2 - 6A + 11I\), we get \(c = -6\) and \(d = 11\). Therefore, \(c + d = -6 + 11 = \mathbf{5}\).

The correct option is A. 5.

\(20\hat{i} + 7\hat{j}\)

\(20\hat{i} + 7\hat{j} + 12\hat{k}\)

\(20\hat{i} + 12\hat{k}\)

\(20\hat{i}\)

The direction of most rapid increase is the gradient, \(\nabla f\). \[\nabla f = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\hat{i} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\hat{j} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\hat{k} = (8x + 7y + 3z^2)\hat{i} + (7x)\hat{j} + (6xz)\hat{k}\] Evaluating at \(P=(1, 0, 2)\): \[\nabla f|_{(1, 0, 2)} = (8(1) + 7(0) + 3(2)^2)\hat{i} + (7(1))\hat{j} + (6(1)(2))\hat{k} = \mathbf{20\hat{i} + 7\hat{j} + 12\hat{k}}\]

The correct option is B. \(20\hat{i} + 7\hat{j} + 12\hat{k}\).

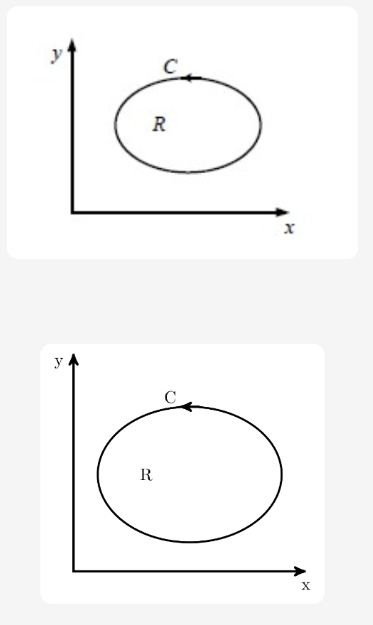

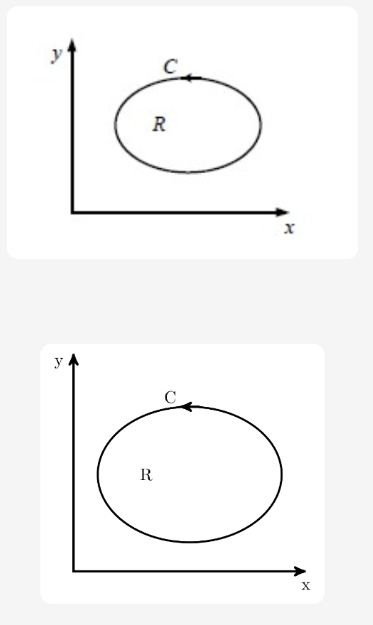

\(\iint_{R} dxdy\)

\(\oint_{C} xdy\)

\(\oint_{C} ydx\)

\(\frac{1}{2}\oint_{C} (xdy - ydx)\)

The area \(A\) of a region \(R\) is given by \(A = \iint_{R} dxdy\). By Green’s Theorem, \(\oint_{C} Mdx + Ndy = \iint_{R} (\frac{\partial N}{\partial x} - \frac{\partial M}{\partial y}) dx dy\).

Option C: \(\oint_{C} ydx\). Here \(M=y, N=0\). Then \(\frac{\partial N}{\partial x} - \frac{\partial M}{\partial y} = 0 - 1 = -1\). Thus, \(\oint_{C} ydx = \iint_{R} (-1) \, dxdy = -A\). This does not represent the area \(A\).

The correct option is C. \(\oint_{C} ydx\).

\(a = 1\)

\(a = 2\)

\(a = 1/2\)

\(a = 1/4\)

For \(f(x)\) to be a valid PDF, \(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) dx = 1\). Since \(e^{-2|x|}\) is an even function: \[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} ae^{-2|x|} dx = 2a \int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-2x} dx = 1\]

Evaluating the integral: \[2a \left[ \frac{e^{-2x}}{-2} \right]_{0}^{\infty} = 1\] \[2a \left[ -\frac{1}{2} (0 - 1) \right] = 1\] \[2a \left( \frac{1}{2} \right) = 1 \implies a = 1\]

The correct option is A. \(a = 1\).